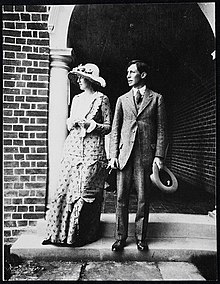

Virginia Woolf

Appearance

Virginia Woolf (25 January 1882 – 28 March 1941), born Adeline Virginia Stephen, was a British writer who is considered to be one of the foremost modernist/feminist literary figures of the twentieth century.

- See also: Orlando: A Biography

Quotes

[edit]

- At this Helen laughed outright. "Nonsense," she said. "You're not a Christian. You've never thought what you are.—And there are lots of other questions," she continued, "though perhaps we can't ask them yet." Although they had talked so freely they were all uncomfortably conscious that they really knew nothing about each other.

"The important questions," Hewet pondered, "the really interesting ones. I doubt that one ever does ask them."

Rachel, who was slow to accept the fact that only a very few things can be said even by people who know each other well, insisted on knowing what he meant.

"Whether we've ever been in love?" she enquired. "Is that the kind of question you mean?"- The Voyage Out (1915), Ch. XI

- On the towpath we met & had to pass a long line of imbeciles. The first was a very tall young man, just queer enough to look twice at, but no more; the second shuffled, & looked aside; & then one realised that every one in that long line was a miserable ineffective shuffling idiotic creature, with no forehead, or no chin, & an imbecile grin, or a wild suspicious stare. It was perfectly horrible. They should certainly be killed.

- Diary entry (9 January 1915), quoted in The Diary of Virginia Woolf, Volume I: 1915–1919, ed. Anne Olivier Bell (1977), p. 13

- An illiterate, underbred book it seems to me; the book of a self-taught working man, and we all know how distressing they are, how egotistic, insistent, raw, striking, and ultimately nauseating. When one can have the cooked flesh, why have the raw?

- Diary entry on James Joyce's Ulysses (16 August 1922), quoted in Virginia Woolf, A Writer's Diary (1953; 1965), p. 47

- Margaret Ll. Davies writes that Janet is dying and will I write on her for The Times – a curious thought, rather: as if it mattered who wrote, or not. But this flooded me with the idea of Janet yesterday. I think writing, my writing, is a species of mediumship. I become the person.

- Entry of 11 July 1937, in A Writer's Diary (1953)

- Here I come to one of the memoir writer's difficulties — one of the reasons why, though I read so many, so many are failures. They leave out the person to whom things happened. The reason is that it is so difficult to describe any human being. So they say: ‘This is what happened’; but they do not say what the person was like to whom it happened. Who was I then? Adeline Virginia Stephen, the second daughter of Leslie and Julia Prinsep Stephen, born on 25th January 1882, descended from a great many people, some famous, others obscure; born into a large connection, born not of rich parents, but of well-to-do parents, born into a very communicative, literate, letter writing, visiting, articulate, late nineteenth century world.

- "A Sketch of the Past" (written 1939, published posthumously)

- The Reverend C. L. Dodgson had no life. He passed through the world so lightly that he left no print. He melted so passively into Oxford that he is invisible.

- Essay "Lewis Carroll" (1939); reprinted in The Moment, and Other Essays (1948)

- For some reason, we know not what, his childhood was sharply severed. It lodged in him whole and entire. He could not disperse it.

- Essay "Lewis Carroll" (1939)

- Dearest,

I want to tell you that you have given me complete happiness. No one could have done more than you have done. Please believe that.

But I know that I shall never get over this: and I am wasting your life. It is this madness. Nothing anyone says can persuade me. You can work, and you will be much better without me. You see I can't write this even, which shows I am right. All I want to say is that until this disease came on we were perfectly happy. It was all due to you. No one could have been so good as you have been, from the very first day till now. Everyone knows that.

V.- Letter to Leonard Woolf (28 March 1941), from The Virginia Woolf Reader (1984) edited by Mitchell A. Leaska, p. 369, ISBN 0156935902

- One cannot grow fine flowers in a thin soil.

- Women and Writing (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1979), p. 54. Also in The Essays of Virginia Woolf: 1929-1932. Hogarth Press. 1986. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-7012-0670-3.

Night and Day (1919)

[edit]- No one can escape the power of language, let alone those of English birth brought up from childhood, as Mrs. Hilbery had been, to disport themselves now in the Saxon plainness, now in the Latin splendor of the tongue, and stored with memories, as she was, of old poets exuberating in an infinity of vocables. Even Katharine was slightly affected against her better judgment by her mother's enthusiasm. Not that her judgment could altogether acquiesce in the necessity for a study of Shakespeare's sonnets as a preliminary to the fifth chapter of her grandfather's biography. Beginning with a perfectly frivolous jest, Mrs. Hilbery had evolved a theory that Anne Hathaway had a way, among other things, of writing Shakespeare's sonnets; the idea, struck out to enliven a party of professors, who forwarded a number of privately printed manuals within the next few days for her instruction, had submerged her in a flood of Elizabethan literature; she had come half to believe in her joke, which was, she said, at least as good as other people's facts, and all her fancy for the time being centered upon Stratford-on-Avon.

- Ch. 24

- "What is this romance?" she mused.

"Ah, that’s the question. I’ve never come across a definition that satisfied me, though there are some very good ones"—he glanced in the direction of his books.

"It’s not altogether knowing the other person, perhaps—it’s ignorance," she hazarded.

"Some authorities say it’s a question of distance—romance in literature, that is—"

"Possibly, in the case of art. But in the case of people it may be—" she hesitated.

Jacob's Room (1922)

[edit]

- The strange thing about life is that though the nature of it must have been apparent to every one for hundreds of years, no one has left any adequate account of it. The streets of London have their map; but our passions are uncharted. What are you going to meet if you turn this corner?

- Ch. 8

The Common Reader (1925)

[edit]

- But can we go to posterity with a sheaf of loose pages, or ask the readers of those days, with the whole of literature before them, to sift our enormous rubbish heaps for our tiny pearls? Such are the questions which the critics might lawfully put to their companions at table, the novelists and poets.

- "How It Strikes a Contemporary"

- Examine for a moment an ordinary mind on an ordinary day. The mind receives a myriad impressions — trivial, fantastic, evanescent, or engraved with the sharpness of steel. From all sides they come, an incessant shower of innumerable atoms; and as they fall, as they shape themselves into the life of Monday or Tuesday, the accent falls differently from of old; the moment of importance came not here but there; so that, if a writer were a free man and not a slave, if he could write what he chose, not what he must, if he could base his work upon his own feeling and not upon convention, there would be no plot, no comedy, no tragedy, no love interest or catastrophe in the accepted style, and perhaps not a single button sewn on as the Bond Street tailors would have it. Life is not a series of gig-lamps symmetrically arranged; life is a luminous halo, a semi-transparent envelope surrounding us from the beginning of consciousness to the end. Is it not the task of the novelist to convey this varying, this unknown and uncircumscribed spirit, whatever aberration or complexity it may display, with as little mixture of the alien and external as possible? We are not pleading merely for courage and sincerity; we are suggesting that the proper stuff of fiction is a little other than custom would have us believe it.

- "Modern Fiction"

- Let us record the atoms as they fall upon the mind in the order in which they fall, let us trace the pattern, however disconnected and incoherent in appearance, which each sight or incident scores upon the consciousness.

- "Modern Fiction"

- Theirs, too, is the word-coining genius, as if thought plunged into a sea of words and came up dripping.

- "Notes on an Elizabethan Play"

- But delightful though it is to indulge in righteous indignation, it is misplaced if we agree with the lady's-maid that high birth is a form of congenital insanity, that the sufferer merely inherits the diseases of his ancestors, and endures them, for the most part very stoically, in one of those comfortably padded lunatic asylums which are known, euphemistically, as the stately homes of England.

- "Outlines: Lady Dorothy Nevill"

- We may enjoy our room in the tower, with the painted walls and the commodious bookcases, but down in the garden there is a man digging who buried his father this morning, and it is he and his like who live the real life and speak the real language.

- For ourselves, who are ordinary men and women, let us return thanks to Nature for her bounty by using every one of the senses she has given us; vary our state as much as possible; turn now this side, now that, to the warmth, and relish to the full before the sun goes down the kisses of youth and the echoes of a beautiful voice singing Catullus. Every season is likeable, and wet days and fine, red wine and white, company and solitude. Even sleep, that deplorable curtailment of the joy of life, can be full of dreams; and the most common actions—a walk, a talk, solitude in one's own orchard—can be enhanced and lit up by the association of the mind. Beauty is everywhere, and beauty is only two finger's-breadth from goodness.

- Humour is the first of the gifts to perish in a foreign tongue.

Mrs Dalloway (1925)

[edit]

- Mrs Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.

- It was enemies one wanted, not friends.

- A whole lifetime was too short to bring out, the full flavour; to extract every ounce of pleasure, every shade of meaning.

- What she loved was this, here, now, in front of her; the fat lady in the cab. Did it matter then, she asked herself, walking towards Bond Street, did it matter that she must inevitably cease completely; all this must go on without her; did she resent it; or did it not become consoling to believe that death ended absolutely? but that somehow in the streets of London, on the ebb and flow of things, here there, she survived. Peter survived, lived in each other, she being part, she was positive, of the trees at home; of the house there, ugly, rambling all to bits and pieces as it was; part of people she had never met; being laid out like a mist between the people she knew best, who lifted her on their branches as she had seen the trees lift the mist, but it spread ever so far, her life, herself.

- But to go deeper, beneath what people said (and these judgements, how superficial, how fragmentary they are!) in her own mind now, what did it mean to her, this thing she called life? Oh, it was very queer. Here was So-and-so in South Kensington; some one up in Bayswater; and somebody else, say, in Mayfair. And she felt quiet continuously a sense of their existence and she felt what a waste; and she felt what a pity; and she felt if only they could be brought together; so she did it. And it was an offering; to combine, to create; but to whom?

An offering for the sake of offering, perhaps. Anyhow, it was her gift. Nothing else had she of the slightest importance; could not think, write, even play the piano. She muddled Armenians and Turks; loved success; hated discomfort; must be liked; talked oceans of nonsense: and to this day, ask her what the Equator was, and she did not know.

All the same, that one day should follow another; Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday; that one should wake up in the morning; see the sky; walk in the park; meet Hugh Whitbread; then suddenly in came Peter; then these roses; it was enough. After that, how unbelievable death was! — that it must end; and no one in the whole world would know how she had loved it all.

- Rigid, the skeleton of habit alone upholds the human frame.

On Being Ill (1926)

- The merest schoolgirl [school girl,] when she falls in love, has Shakespeare or Keats to speak her mind for her; but let a sufferer [try to] describe a pain in his head to a doctor and language at once runs dry.

To the Lighthouse (1927)

[edit]

- Could loving, as people called it, make her and Mrs Ramsay one? for it was not knowledge but unity that she desired, not inscription on tablets, nothing that could be written in any language known to men, but intimacy itself, which is knowledge, she had thought, leaning her head on Mrs Ramsay's knee.

- Part I, Ch. 9

- She felt this thing that she called life terrible, hostile, and quick to pounce on you if you gave it a chance. There were the eternal problems: suffering; death; the poor. There was always a woman dying of cancer even here. And yet she had said to all these children, You shall go through with it.

- Part I, Ch. 10

- She had done the usual trick – been nice. She would never know him. He would never know her. Human relations were all like that, she thought, and the worst (if it had not been for Mr Bankes) were between men and women. Inevitably these were extremely insincere.

- Part I, Ch. 17

- For our penitence deserves a glimpse only; our toil respite only.

- Part II, Ch. 3

- "Like a work of art," she repeated, looking from her canvas to the drawing-room steps and back again. She must rest for a moment. And, resting, looking from one to the other vaguely, the old question which transversed the sky of the soul perpetually, the vast, the general question which was apt to particularise itself at such moments as these, when she released faculties that had been on the strain, stood over her, paused over her, darkened over her. What is the meaning of life? That was all — a simple question; one that tended to close in on one with years. The great revelation had never come. The great revelation perhaps never did come. Instead there were little daily miracles, illuminations, matches struck unexpectedly in the dark; here was one. This, that, and the other; herself and Charles Tansley and the breaking wave; Mrs. Ramsay bringing them together; Mrs. Ramsay saying, "Life stand still here"; Mrs. Ramsay making of the moment something permanent (as in another sphere Lily herself tried to make of the moment something permanent) — this was of the nature of a revelation. In the midst of chaos there was shape; this eternal passing and flowing (she looked at the cloud going and the leaves shaking) was struck into stability. Life stand still here, Mrs. Ramsay said. "Mrs. Ramsay! Mrs. Ramsay!" she repeated. She owed it all to her.

- Part III, Ch. 3

- Mrs Ramsay sat silent. She was glad, Lily thought, to rest in silence, uncommunicative; to rest in the extreme obscurity of human relationships. Who knows what we are, what we feel? Who knows even at the moment of intimacy, This is knowledge? Aren't things spoilt then, Mrs Ramsay may have asked (it seemed to have happened so often, this silence by her side) by saying them?

- Part III, Ch. 5

- But one only woke people if one knew what one wanted to say to them. And she wanted to say not one thing, but everything. Little words that broke up the thought and dismembered it said nothing. 'About life, about death; about Mrs Ramsay' – no, she thought, one could say nothing to nobody.

- Part III, Ch. 5

- She alone spoke the truth; to her alone could he speak it. That was the source of her everlasting attraction for him, perhaps; she was a person to whom one could say what came into one's head.

- Part III, Ch. 9

A Room of One's Own (1929)

[edit]

- A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.

- Ch. 1, p. 4

- When a subject is highly controversial — and any question about sex is that — one cannot hope to tell the truth. One can only show how one came to hold whatever opinion one does hold. One can only give one's audience the chance of drawing their own conclusions as they observe the limitations, the prejudices, the idiosyncrasies of the speaker.

- Ch. 1, p. 4

- No need to hurry. No need to sparkle. No need to be anybody but oneself.

- Ch. 1, p. 17

- The beauty of the world which is so soon to perish, has two edges, one of laughter, one of anguish, cutting the heart asunder.

- Ch. 1, p. 17

- The human frame being what it is, heart, body and brain all mixed together, and not contained in separate compartments as they will be no doubt in another million years, a good dinner is of great importance to good talk. One cannot think well, love well, sleep well, if one has not dined well.

- Ch. 1, p. 18

- If truth is not to be found on the shelves of the British Museum, where, I asked myself, picking up a notebook and a pencil, is truth?

- Ch. 2, p. 25

- Have you any notion how many books are written about women in the course of one year? Have you any notion how many are written by men? Are you aware that you are, perhaps, the most discussed animal in the universe?

- Ch. 2, p. 26

- Life for both sexes — and I looked at them, shouldering their way along the pavement — is arduous, difficult, a perpetual struggle. It calls for gigantic courage and strength. More than anything, perhaps, creatures of illusion as we are, it calls for confidence in oneself. Without self-confidence we are as babes in the cradle. And how can we generate this imponderable quality, which is yet so invaluable, most quickly? By thinking that other people are inferior to one self. By feeling that one has some innate superiority — it may be wealth, or rank, a straight nose, or the portrait of a grandfather by Romney — for there is no end to the pathetic devices of the human imagination — over other people.

- Ch. 2, p. 35

- Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size.

- Ch. 2, p. 35

- [Women] Are they capable of education or incapable? Napoleon thought them incapable. Dr. Johnson thought the opposite. Have they souls or have they not souls? Some savages say they have none. Others, on the contrary, maintain that women are half divine and worship them on that account. Some sages hold that they are shallower in the brain; others that they are deeper in the consciousness. Goethe honoured them; Mussolini despises them. Wherever one looked men thought about women and thought differently. It was impossible to make head or tail of it all, I decided, glancing with envy at the reader next door who was making the neatest abstracts, headed often with an A or a B or a C, while my own notebook rioted with the wildest scribble of contradictory jottings. It was distressing, it was bewildering, it was humiliating. Truth had run through my fingers. Every drop had escaped.

- Ch. 2,

- Fiction is like a spider's web, attached ever so lightly perhaps, but still attached to life at all four corners. Often the attachment is scarcely perceptible; Shakespeare's plays, for instance, seem to hang there complete by themselves. But when the web is pulled askew, hooked up at the edge, torn in the middle, one remembers that these webs are not spun in midair by incorporeal creatures, but are the work of suffering human beings, and are attached to the grossly material things, like health and money and the houses we live in.

- Ch. 3, pp. 43-44

- I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.

- Ch. 3, p. 51

- Very often misquoted as "For most of history, Anonymous was a woman."

- For it needs little skill in psychology to be sure that a highly gifted girl who had tried to use her gift for poetry would have been so thwarted and hindered by other people, so tortured and pulled asunder by her own contrary instincts, that she must have lost her health and sanity to a certainty.

- Ch. 3, p. 51

- Literature is strewn with the wreckage of men who have minded beyond reason the opinions of others.

- Ch. 3, p. 58

- The history of men's opposition to women's emancipation is more interesting perhaps than the story of that emancipation itself.

- It is the nature of the artist to mind excessively what is said about him. Literature is strewn with the wreckage of men who have minded beyond reason the opinions of others.

- Lock up your libraries if you like; but there is no gate, no lock, no bolt that you can set upon the freedom of my mind.

- Ch. 4, p. 90

- I told you in the course of this paper that Shakespeare had a sister; but do not look for her in Sir Sidney Lee's life of the poet. She died young — alas, she never wrote a word... Now my belief is that this poet who never wrote a word and was buried at the cross-roads still lives. She lives in you and in me, and in many other women who are not here to-night, for they are washing up the dishes and putting the children to bed. But she lives; for great poets do not die; they are continuing presences; they need only the opportunity to walk among us in the flesh.

- Ch. 6, p. 117)

- My belief is that if we live another century or so — I am talking of the common life which is the real life and not of the little separate lives which we live as individuals — and have five hundred a year each of us and rooms of our own; if we have the habit of freedom and the courage to write exactly what we think; if we escape a little from the common sitting-room and see human beings not always in their relation to each other but in relation to reality; and the sky, too, and the trees or whatever it may be in themselves; if we look past Milton's bogey, for no human being should shut out the view; if we face the fact, for it is a fact, that there is no arm to cling to, but that we go alone and that our relation is to the world of reality and not only to the world of men and women, then the opportunity will come and the dead poet who was Shakespeare's sister will put on the body which she has so often laid down. Drawing her life from the lives of the unknown who were her forerunners, as her brother did before her, she will be born. As for her coming without that preparation, without that effort on our part, without that determination that when she is born again she shall find it possible to live and write her poetry, that we cannot expect, for that would be impossible. But I maintain that she would come if we worked for her, and that so to work, even in poverty and obscurity, is worth while.

- Ch. 6, pp. 117-118

Orlando: A Biography (1928)

[edit]

- He — for there could be no doubt of his sex, though the fashion of the time did something to disguise it — was in the act of slicing at the head of a Moor which swung from the rafters.

- Ch. 1, first lines

- At the age of thirty, or thereabouts, this young Nobleman had not only had every experience that life has to offer, but had seen the worthlessness of them all. Love and ambition, women and poets were all equally vain. Literature was a farce. The night after reading Greene's Visit to a Nobleman in the Country, he burnt in a great conflagration fifty-seven poetical works, only retaining 'The Oak Tree', which was his boyish dream and very short. Two things alone remained to him in which he now put any trust: dogs and nature; an elk-hound and a rose bush. The world, in all its variety, life in all its complexity, had shrunk to that. Dogs and a bush were the whole of it.

- Ch. 2

- Time, unfortunately, though it makes animals and vegetables bloom and fade with amazing punctuality, has no such simple effect upon the mind of man. The mind of man, moreover, works with equal strangeness upon the body of time. An hour, once it lodges in the queer element of the human spirit, may be stretched to fifty or a hundred times its clock length; on the other hand, an hour may be accurately represented on the timepiece of the mind by one second. This extraordinary discrepancy between time on the clock and time in the mind is less known than it should be and deserves fuller investigation.

- Ch. 2

- While fame impedes and constricts, obscurity wraps about a man like a mist; obscurity is dark, ample, and free; obscurity lets the mind take its way unimpeded. Over the obscure man is poured the merciful suffusion of darkness. None knows where he goes or comes. He may seek the truth and speak it; he alone is free; he alone is truthful, he alone is at peace.

- Ch. 2

- Better was it to go unknown and leave behind you an arch, a potting shed, a wall where peaches ripen, than to burn like meteor and leave no dust.

- Ch. 2

- The trumpeters, ranging themselves side by side in order, blow one terrific blast: —

'THE TRUTH!

at which Orlando woke.

He stretched himself. He rose. He stood upright in complete nakedness before us, and while the trumpets pealed Truth! Truth! Truth! we have no choice left but confess — he was a woman.- Ch. 3

- The sound of the trumpets died away and Orlando stood stark naked. No human being, since the world began, has ever looked more ravishing. His form combined in one the strength of a man and a woman's grace.

- Ch. 3

- We may take advantage of this pause in the narrative to make certain statements. Orlando had become a woman — there is no denying it. But in every other respect, Orlando remained precisely as he had been. The change of sex, though it altered their future, did nothing whatever to alter their identity. Their faces remained, as their portraits prove, practically the same. His memory — but in future we must, for convention's sake, say 'her' for 'his,' and 'she' for 'he' — her memory then, went back through all the events of her past life without encountering any obstacle. Some slight haziness there may have been, as if a few dark drops had fallen into the clear pool of memory; certain things had become a little dimmed; but that was all. The change seemed to have been accomplished painlessly and completely and in such a way that Orlando herself showed no surprise at it. Many people, taking this into account, and holding that such a change of sex is against nature, have been at great pains to prove (1) that Orlando had always been a woman, (2) that Orlando is at this moment a man. Let biologists and psychologists determine. It is enough for us to state the simple fact; Orlando was a man till the age of thirty; when he became a woman and has remained so ever since.

- Ch. 3

- No passion is stronger in the breast of man than the desire to make others believe as he believes. Nothing so cuts at the root of his happiness and fills him with rage as the sense that another rates low what he prizes high. Whigs and Tories, Liberal party and Labour party — for what do they battle except their own prestige?

- Ch. 3

- The chief charges against her were (1) that she was dead, and therefore could not hold any property; (2) that she was a woman which amounts to much the same thing ...

- Ch. 4

- Something, perhaps, we must believe in, and as Orlando, we have said, had no belief in the usual divinities she bestowed her credulity upon great men — yet with a distinction. Admirals, soldiers, statesmen, moved her not at all. But the very thought of a great writer stirred her to such a pitch of belief that she almost believed him to be invisible. Her instinct was a sound one. One can only believe entirely, perhaps, in what one cannot see.

- Ch. 4

- Only those who have little need of the truth, and no respect for it — the poets and novelists — can be trusted to do it, for this is one of the cases where the truth does no exist. Nothing exists. The whole thing is a miasma — a mirage.

- Ch. 4

- Society is the most powerful conception in the world and society has no existence whatsoever.

- Ch. 4

- Old Madame du Deffand and her friends talked for fifty years without stopping. And of it all, what remains? Perhaps three witty sayings.

- Ch. 4

- The hostess is our modern Sibyl. She is a witch who lays her guests under a spell. In this house they think themselves happy; in that witty; in a third profound. It is all an illusion (which is nothing against it, for illusions are the most valuable and necessary of all things, and she who can create one is among the world's greatest benefactors), but as it is notorious that illusions are shattered by conflict with reality, so no real happiness, no real wit, no real profundity are tolerated where the illusion prevails.

- Ch. 4

- As long as she thinks of a man, nobody objects to a woman thinking.

- Ch. 6

- Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978, ISBN 0-15-694960-1

- But look — he flicks his hand to the back of his neck. For such gesture one falls hopelessly in love for a lifetime.

- p. 30

- Here on this ring of grass we have sat together, bound by the tremendous power of some inner compulsion. The trees wave, the clouds pass. The time approaches when these soliloquies shall be shared. We shall not always give out a sound like a beaten gong as one sensation strikes and then another. Children, our lives have been gongs striking; clamour and boasting; cries of despair; blows on the nape of the neck in gardens.

- pp. 39-40

- You are not listening to me. You are making phrases about Byron. And while you gesticulate, with your cloak, your cane, I am trying to expose a secret told to nobody yet; I am asking you (as I stand with my back to you) to take my life in your hands and tell me whether I am doomed always to cause repulsion in those I love?

- Bernard, section III

- For I am more selves than Neville thinks. We are not simple as our friends would have us to meet their needs. Yet love is simple.

- Bernard, section III

- Among the tortures and devastations of life is this then — our friends are not able to finish their stories.

- Ch. II

- ‘Now,’ said Neville, ‘my tree flowers. My heart rises. All oppression is relieved. All impediment is removed. The reign of chaos is over. He has imposed order. Knives cut again.’ [...]

‘Here is Percival,’ said Bernard, ‘[...] We [...] now come nearer; and shuffling closer on our perch in this restaurant where everybody’s interests are at variance, and the incessant passage of traffic chafes us with distractions, and the door opening perpetually its glass cage solicits us with myriad temptations and offers insults and wounds to our confidence — sitting together here we love each other and believe in our own endurance.’- section IV

- Now, through my own infirmity I recover what he was to me: my opposite. Being naturally truthful, he did not see the point of these exaggerations, and was borne on by a natural sense of the fitting, was indeed a great master of the art of living so that he seems to have lived long, and to have spread calm round him, indifference one might almost say, certainly to his own advancement, save that he had also great compassion. [...] We have no ceremonies, only private dirges and no conclusions, only violent sensations, each separate. Nothing that has been said meets our case. [...] After a long lifetime, loosely, in a moment of revelation, I may lay hands on it, but now the idea breaks in my hand. Ideas break a thousand times for once that they globe themselves entire. [...] I am yawning. I am glutted with sensations. I am exhausted with the strain and the long, long time — twenty-five minutes, half an hour — that I have held myself alone outside the machine.

- Bernard on Percival, section V

- Things have dropped from me. I have outlived certain desires; I have lost friends, some by death... others through sheer inability to cross the street.

- p. 186

- Yet there are moments when the walls of the mind grow thin; when nothing is unabsorbed, and I could fancy that we might blow so vast a bubble that the sun might set and rise in it and we might take the blue of midday and the black of midnight and be cast off and escape from here and now.

- p. 224

- I like the copious, shapeless, warm, not so very clever, but extremely easy and rather coarse aspect of things; the talk of men in clubs and public-houses; of miners half naked in drawers — the forthright, perfectly unassuming, and without end in view except dinner, love, money and getting along tolerably; that which is without great hopes, ideals, or anything of that kind; what is unassuming except to make a tolerably, good job of it. I like all that.

- p. 246

- We have dined well. The fish, the veal cutlets, the wine have blunted the sharp tooth of egotism. Anxiety is at rest. The vainest of us, Louis perhaps, does not care what people think. Neville's tortures are at rest. Let others prosper — that is what he thinks. Susan hears the breathing of all her children safe asleep. Sleep, sleep, she murmurs. Rhoda has rocked her ships to shore. Whether they have foundered, whether they have anchored, she cares no longer.

- Bernard, section VIII

- ‘The flower,’ said Bernard, ‘the red carnation that stood in the vase on the table of the restaurant when we dined together with Percival, is become a six-sided flower; made of six lives.’

- section VIII

- *Was there no sword, nothing with which to batter down these walls, this protection, this begetting of children and living behind curtains, and becoming daily more involved and committed, with books and pictures? Better burn one's life out like Louis, desiring perfection; or like Rhoda leave us, flying past us to the desert; or choose one out of millions and one only like Neville; better be like Susan and love and hate the heat of the sun or the frost-bitten grass; or be like Jinny, honest, an animal. All had their rapture; their common feeling with death; something that stood them in stead. Thus I visited each of my friends in turn, trying, with fumbling fingers, to prise open their locked caskets. I went from one to the other holding my sorrow — no, not my sorrow but the incomprehensible nature of this our life — for their inspection. Some people go to priests; others to poetry; I to my friends, I to my own heart, I to seek among phrases and fragments something unbroken — I to whom there is not beauty enough in moon or tree; to whom the touch of one person with another is all, yet who cannot grasp even that, who am so imperfect, so weak, so unspeakably lonely. There I sat.

- Bernard, section IX

- Our friends, how seldom visited, how little known — it is true; and yet, when I meet an unknown person, and try to break off, here at this table, what I call “my life”, it is not one life that I look back upon; I am not one person; I am many people; I do not altogether know who I am — Jinny, Susan, Neville, Rhoda, or Louis; or how to distinguish my life from theirs.

- Bernard, section IX

Three Guineas (1938)

[edit]

- Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1966, ISBN 0-156-90177-3

- Though we see the same world, we see it through different eyes. Any help we can give you must be different from that you can give yourselves, and perhaps the value of that help may lie in the fact of that difference.

- Ch. 1, p. 18

- Directly the mulberry tree begins to make you circle, break off. Pelt the tree with laughter.

- Ch. 2, p. 80

- The outsider will say, "in fact, as a woman, I have no country. As a woman I want no country. As a woman my country is the whole world." And if, when reason has said its say, still some obstinate emotion remains, some love of England dropped into a child's ears by the cawing of rooks in an elm tree, by the splash of waves on a beach, or by English voices murmuring nursery rhymes, this drop of pure, if irrational, emotion she will make serve her to give to England first what she desires of peace and freedom for the whole world.

- Ch. 3, p. 109

Between the Acts (1941)

[edit]- 'That was the burden,' she mused, 'laid on me in the cradle; murmured by waves; breathed by restless elm trees; crooned by singing women; what we must rememeber; what we would forget.'

- Words rose above the intolerably laden dumb oxen plodding through the mud. Words without meaning - wonderful words.

- They never pulled the curtains till it was too dark to see, nor shut the windows till it was too cold. Why shut out the day before it was over? The flowers were still bright; the birds chirped. You could see more in the evening often when nothing interrupted, when there was no fish to order, no telephone to answer.

- Mrs Swithin took her knitting from the table. 'Did you feel,' she asked, 'what he said: we act different parts but are the same?'

- 'Yes,' Isa answered. 'No,' she added. It was Yes, No. Yes, yes, yes, the tide rushed out embracing. No, no, no, it contracted.

- The flowers flashed before they faded. She watched them flash.

- Books are the mirrors of the soul.

The Death of the Moth and Other Essays (1942)

[edit]- The artist after all is a solitary being.

- "The Historian and 'The Gibbon'"

- Once you begin to take yourself seriously as a leader or as a follower, as a modern or as a conservative, then you become a self-conscious, biting, and scratching little animal whose work is not of the slightest value or importance to anybody.

- "A Letter to a Young Poet"

- Lines slip easily down the accustomed grooves. The old designs are copied so glibly that we are half inclined to think them original, save for that very glibness.

- "A Letter to a Young Poet"

- I mean, what is a woman? I assure you, I do not know. I do not believe that you know. I do not believe that anybody can know until she has expressed herself in all the arts and professions open to human skill.

- "Professions for Women"

- Outwardly, what is simpler than to write books? Outwardly, what obstacles are there for a woman rather than for a man? Inwardly, I think, the case is very different; she has still many ghosts to fight, many prejudices to overcome. Indeed it will be a long time still, I think, before a woman can sit down to write a book without finding a phantom to be slain, a rock to be dashed against. And if this is so in literature, the freest of all professions for women, how is it in the new professions which you are now for the first time entering?

- "Professions for Women"

The Moment and Other Essays (1948)

[edit]

- If you do not tell the truth about yourself you cannot tell it about other people.

- "The Leaning Tower", lecture delivered to the Workers' Educational Association, Brighton (May 1940)

Granite and Rainbow (1958)

[edit]

- The extraordinary woman depends on the ordinary woman. It is only when we know what were the conditions of the average woman's life ... it is only when we can measure the way of life and the experience of life made possible to the ordinary woman that we can account for the success or failure of the extraordinary woman as a writer.

- "Women and Fiction"

- But the novels of women were not affected only by the necessarily narrow range of the writer's experience. They showed, at least in the nineteenth century, another characteristic which may be traced to the writer's sex. In Middlemarch and in Jane Eyre we are conscious not merely of the writer's character, as we are conscious of the character of Charles Dickens, but we are conscious of a woman's presence — of someone resenting the treatment of her sex and pleading for its rights.

- "Women and Fiction"

- If, then, one should try to sum up the character of women's fiction at the present moment, one would say that it is courageous; it is sincere; it keeps closely to what women feel. It is not bitter. It does not insist upon its femininity.

- "Women and Fiction"

- In the past, the virtue of women's writing often lay in its divine spontaneity ... But it was also, and much more often, chattering and garrulous ... In future, granted time and books and a little space in the house for herself, literature will become for women, as for men, an art to be studied. Women's gift will be trained and strengthened. The novel will cease to be the dumping-ground for the personal emotions. It will become, more than at present, a work of art like any other, and its resources and its limitations will be explored.

- "Women and Fiction"

Books and Portraits (1977)

[edit]- The strongest natures, when they are influenced, submit the most unreservedly: it is perhaps a sign of their strength. But that Thoreau lost any of his own force in the process, or took on permanently any colours not natural to himself the readers of his books will certainly deny. The Transcendentalist movement, like most movements of vigour, represented the effort of one or two remarkable people to shake off the old clothes which had become uncomfortable to them and fit themselves more closely to what now appeared to them to be the realities.

- "Thoreau"

Moments of Being (1939-1940)

[edit]- That great Cathedral space which was childhood.

- "A Sketch of the Past"

A Moment's Liberty (1990)

[edit]

- Our patience wore rather thin. Visitors do tend to chafe one, though impeccable as friends. L. and I discussed this. He says that with people in the house his hours of positive pleasure are reduced to one; he has I forget how many hours of negative pleasure; and a respectable margin of the acutely unpleasant. Are we growing old?

- 5 April 1918

- Morgan has the artist's mind; he says the simple things that clever people don't say; I find him the best of critics for that reason. Suddenly out comes the obvious thing that one has overlooked.

- 6 November 1919

- This last week L. has been having a little temperature in the evening, due to malaria, and that due to a visit to Oxford; a place of death and decay. I'm almost alarmed to see how entirely my weight rests on his prop. And almost alarmed to see how intensely I'm specialised. My mind turned by anxiety, or other cause, from its scrutiny of blank paper, is like a lost child – wandering the house, sitting on the bottom step to cry.

- 5 December 1919

- We have been to Rodmell, and as usual I come home depressed – for no reason. Merely moods. Have other people as many as I have? That I shall never now. And sometimes I suppose that even if I came to the end of my incessant search into what people are and feel I should know nothing still.

- 23 May 1921

- I have seen very few people. Nessa came again. How painful these meetings are! Let me try to analyse. Perhaps it is that we both feel that we can exist independently of the other. The door shuts between us, and life flows on again and completely removes the trace. That is an absurd exaggeration.

- 4 February 1922

- Neither of us knows what the public will think. There's no doubt in my mind that I have found out how to begin (at forty) to say something in my own voice; and that interests me so that I feel I can go ahead without praise.

- 26 July 1922

- A desire for children, I suppose; for Nessa's life; for the sense of flowers breaking all round me involuntarily. [...] Years and years ago, after the Lytton affair, I said to myself, walking up the hill at Bayreuth, never pretend that the things you haven't got are not worth having; good advice I think. And then I went on to say to myself that one must like things for themselves; or rather, rid them of their bearing upon one's personal life. One must venture on to the things that exist independently of oneself. Now this is very hard for young women to do. Yet I got satisfaction from it. And now, married to L., I never have to make the effort. Perhaps I have been to happy for my soul's good? And does some of my discontent come from feeling that?

- 2 January 1923

- Even Morgan seems to me to be based on some hidden rock. Talking of Proust and Lawrence he said he'd prefer to be Lawrence; but much rather would be himself. He is aloof, serene, a snob, he says, reading masterpieces only.

- Tuesday 18 September 1923

- I must try to set aside half an hour in some part of my day, and consecrate it to diary writing. Give it a name and a place, and then perhaps, such is the human mind, I shall come to think it a duty, and disregard other duties for it.

- Wednesday 8 April 1925

- Happiness is to have a little string onto which things will attach themselves.

- Monday 20 April 1925

- In brain and insight she is not as highly organised as I am. But then she is aware of this, and so lavishes on me the maternal protection which, for some reason, is what I have always most wished from everyone.

- Monday 21 December 1925

- As for the soul: why did I say I would leave it out? I forget. And the truth is, one can't write directly about the soul. Looked at, it vanishes; but look at the ceiling, at Grizzle, at the cheaper beasts in the Zoo which are exposed to walkers in Regent's Pak, and the soul slips in. Mrs Webb's book has made me think a little what I could say of my own life. But then there were causes in her life: prayer; principle. None in mine. Great excitability and search after something. Great content – almost always enjoying what I'm at, but with constant change of mood. I don't think I'm ever bored. Yet I have some restless searcher in me. Why is there not a discovery in life? Something one can lay hands on and say 'This is it'? What is it? And shall I die before I can find it? Then (as I was walking through Russell Square last night) I see mountains in the sky: the great clouds, and the moon which is risen over Persia; I have a great and astonishing sense of something there, which is 'it' – A sense of my own strangeness, walking on the earth is there too. Who am I, what am I, and so on; these questions are always floating about in me. Is that what I meant to say? Not in the least. I was thinking about my own character; not about the universe. Oh and about society again; dining with Lord Berners at Clive's made me think that. How, at a certain moment, I see through what I'm saying; detest myself; and wish for the other side of the moon; reading alone, that is.

- Saturday 27 February 1926

- I am amused at my relations with her: left so ardent in January – and now what? Also I like her presence and her beauty. Am I in love with her? But what is love? Her being 'in love' with me, excites and flatters; and interests. What is this 'love'?

- Thursday 20 May 1926

- Happily, at forty-six I still feel as experimental and on the verge of getting at the truth as ever.

- Saturday 21 April, 1929

- A State of Mind. Woke up perhaps at 3. Oh its beginning it coming – the horror – physically like a painful wave swelling about the heart – tossing me up. I'm unhappy unhappy! Down – God, I wish I were dead. Pause. But why am I feeling like this? Let me watch the wave rise. I watch. Vanessa. Children. Failure. Yes, I detect that. Failure failure. (The wave rises). Oh they laughed at my taste in green paint. Wave crashes. I wish I were dead! I've only a few years to live I hope. I can't face this horror any more – (this is the wave spreading out over me). This goes on; several times, with varieties of horror. Then, at the crisis, instead of the pain remaining intense, it becomes rather vague. I doze. I wake with a start. The wave again! The irrational pain: the sense of failure; generally some specific incident, as for example my taste in green paint, or buying a new dress, or asking Dadie for the week-end, tacked on. At last I say, watching as dispassionately as I can, Now take a pull of yourself. No more of this. I shove to throw to batter down. I begin to march blindly forward. I feel obstacles go down. I say it doesn't matter. Nothing matters. I become rigid and straight, and sleep again, and half wake and feel the wave beginning and watch the light whitening and wonder how, this time, breakfast and daylight will overcome it; and then hear L. in the passage and simulate, for myself as well as for him, great cheerfulness; and generally am cheerful, by the time breakfast is over. Does everyone go through this state? Why have I so little control? It is the case of much waste and pain in my life.

- Wednesday 15 September, 1926

- What a born melancholiac I am! The only way I keep afloat is by working. Directly I stop working I feel that I am sinking down, down. And as usual, I feel that if I sink further I shall reach the truth. That is the only mitigation; a kind of nobility. Solemnity. Work, reading, writing, are all disguising; and relations with other people. Yes, even having children wold be useless.

- Sunday 23 June, 1929

- Lord, how I praise God that I had a bent strong enough to coerce every minute of my life since I was born! This fiddling and drifting and not impressing oneself upon anything – this always refraining and fingering and cutting things up into little jokes and facetiousness – that's what's so annihilating. Yet given little money, little looks, no special gift – what can one do? How could one battle? How could one leap on the back of life and wring its scruff?

- Thursday 20 February, 1930

- I will use these last pages to sum up our circumstances. A map of the world. [...]

I seldom see Lytton; that is true. The reason is that we don't fit in, I imagine, to his parties nor he to ours; but that if we can meet in solitude, all goes as usual. Yet what do one's friends mean to one, if one only sees them eight times a year? [...]

I use my friends rather as giglamps: there's another field I see; by your light. Over there's a hill. I widen my landscape.- Tuesday 2 September, 1930

- Very much screwed in the head by trying to get Roger's marriage chapter into shape; and also warmed by L. saying last night that he was fonder of me than I of him. A discussion as to which would mind the other's death most. He said he depended more upon our common life than I did. He gave the garden as an instance. He said I live more in a world of my own. I go for long walks alone. So we argued. I was very happy to think I was so much needed. Its strange how seldom one feels this: yet 'life in common' is an immense reality.

- Friday 28 April, 1939

Misattributed

[edit]- Thought and theory must precede all salutary action; yet action is nobler in itself than either thought or theory.

- Sometimes ascribed to Virginia Woolf, but it appeared as early as 1854 in Anna Jameson's A Commonplace Book of Thoughts, Memories and Fancies, where it is ascribed to William Wordsworth.

- Writing is like sex. First you do it for love, then you do it for your friends, and then you do it for money.

- The Quote Investigator traces the origin of such statements to The Intimate Notebooks of George Jean Nathan (1932), where the diarist states:

- We were sitting one morning two Summers ago, Ferenc Molnár, Dr. Rudolf Kommer and I, in the little garden of a coffee-house in the Austrian Tyrol. “Your writing?” we asked him. “How do you regard it?” Languidly he readjusted the inevitable monocle to his eye. “Like a whore,” he blandly ventured. “First, I did it for my own pleasure. Then I did it for the pleasure of my friends. And now — I do it for money.”

Quotes about Woolf

[edit]- The English writers who had a big influence on me during my adolescence were Sir Walter Scott, Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters, Charles Dickens, Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, James Joyce, D.H. Lawrence, and Virginia Woolf.

- Of the modern writers, Virginia Woolf is one who consistently attempted to place women at the center of her thinking. But she did not do it with the bold and inclusive sweep of Sappho. She did it awkwardly and with apology, with a tone of self-deprecation. This is apparent, for example, in A Room of One's Own, in its style and tone and in its apparent random "female" ambience of thought hither and yon, an innovation to mask the real power of her intellect.

- Bettina Aptheker Tapestries of Life: Women's Work, Women's Consciousness, and the Meaning of Daily Experience (1989)

- I now think tragedy is not foul deeds done to a person (usually noble in some manner) but rather that tragedy is irresolvable conflict. Both sides/ideas are right. Plot involves fragmentary reality, and it might involve composite reality. Fragmentary reality is the view of the individual. Composite reality is the community or state view. Fragmentary reality is always set against composite reality. Virginia Woolf did this by creating fragmentary monologues and for a while this was all the rage in literature. She was a genius. In the hands of the merely talented it came off like gibberish.

- I cannot say I am a citizen of the world as Virginia Woolf, speaking as an Anglo woman born to economic means, declared herself; nor can I make the same claim to U.S. citizenship as Adrienne Rich does despite her universal feeling for humanity. As a mestiza born to the lower strata, I am treated at best, as a second class citizen, at worst, as a non-entity. I am commonly perceived as a foreigner everywhere I go, including in the United States and in Mexico. This international perception is based on my color and features. I am neither black nor white. I am not light skinned and cannot be mistaken for "white"; because my hair is so straight I cannot be mistaken for "black." And by U.S..standards and according to some North American Native Americans, I cannot make official claims to being india.

- Ana Castillo "A Countryless Woman" in Massacre of the Dreamers: Essays on Xicanisma (1994)

- I don't think we read George Eliot, [Jane Austen]], Virginia Woolf, or Flannery O'Connor as "women writers" anymore, but as vital voices of their time. I know that, for instance, Toni Morrison will be read in this fashion. She is already. The point we're striving for is one at which the criteria for the work is its worth to readers, its excellence, the qualities that shine out and endure.

- 1993 interview in Conversations with Louise Erdrich and Michael Dorris edited by Allan Chavkin and Nancy Feyl Chavkin (1994)

- Not surprisingly, a valorization of the body has been present in nearly all the literature of "second wave" 20th-century feminism, as it has characterized the literature produced by the anti-colonial revolt and by the descendants of the enslaved Africans. On this ground, across great geographic and cultural boundaries, Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own (1929) anticipates Aimé Cesaire's Return to the Native Land (1938), when she mockingly scolds her female audience and, behind it, a broader female world, for not having managed to produce anything but children.

- Silvia Federici Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation (2004)

- I would like to have written Orlando (laughs). But I'm very far from that!

- Rosario Ferré interview in Backtalk: Women Writers Speak Out by Donna Marie Perry (1993)

- [S]ome economic awareness may even be a prerequisite to the full appreciation of [some] books, plays, and operas. Virginia Woolf's Orlando must be quite bewildering to the economically ignorant.

- Martin Gerhard Giesbrecht, The Evolution of Economic Society: An Introduction to Economics (1972) Ch. 11, On Further Study, p. 329.

- Writing is making sense of life. You work your whole life and perhaps you've made sense of one small area. Virginia Woolf did this incomparably. And the complexity of her human relationships, the economy with which she managed to portray them... staggering…(Was Woolf a big influence when you began writing?) NG: Midway, I think-after I'd been writing for about five years. She can be a very dangerous influence on a young writer. It's easy to fall into the cadence. But the content isn't there...

- 1979 and 1980 interview in Conversations with Nadine Gordimer edited by Nancy Topping Bazin and Marilyn Dallman Seymour (1990)

- Her genius was intensely feminine and personal—private almost. To read one of her books was (if you liked it) to receive a letter from her, addressed specially to you.

- Christopher Isherwood, Exhumations (1966), p. 133; quoted in The Literature 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Novelists, Playwrights, and Poets of All Time (2008) by Daniel S. Burt, p. 179

- Nothing is more destructive of the spirit and ultimately of creativity than false meekness, anger that does not know its own name. And nothing is more freeing for a woman (or for a woman writer) than giving up the pleasures of masochism and beginning to fight. But we must always remember that fighting is only a first step. As Virginia Woolf points out in A Room of One's Own, many women's books have been destroyed by the rage and bitterness at their own centers. Rage opens the doors into the spirit, but then the spirit must be nurtureed.

- Erica Jong "Blood and Guts: The Tricky Problem of Being a Woman Writer in the Late Twentieth Century" in The Writer on Her Work edited by Janet Sternburg (2000)

- How begin to describe the permission Woolf’s feminism and artistry bestowed on the hopeful beginner? For me, her work, which never panders, was a reliable antidote to literary men’s scorn or disregard. Her novels demonstrated that despised domesticity, including dinner parties and shopping, could be transformed into unrivaled art.

- Alix Kates Shulman https://bookmarks.reviews/five-books-that-made-me-a-feminist/ “Five Books that Made me a Feminist”] (2019)

- As women readers have articulated not just separate taste, a separate list of best-sellers, favorites, but also a developing network we can call culture, Woolf's role in this culture has become clearer, more obviously key. She wrote about textured lives, the secret currents between women, towards each other, against men, even against each other, but always with a piercing consciousness of sexual conflict. Many of us have imitated/will imitate Woolf to discover what she has to offer in the way of style and vision. And since so many women read and use Woolf, her work becomes familiar, "easier."

- Melaine Kaye/Kantrowitz "Culture-Making: Lesbian Classics in the Year 2000?" in The Issue is Power (1992)

- I know that Virginia Woolf's entire literary project was to find the space, the frozen moment in time, where the individual might matter, because whenever time, that is to say, history intervened, the individual was lost....And Virginia Woolf went mad the last time and killed herself at least partly because it was another war, and who could bear such a thing?

- Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz "While Patriarchy Explodes: Writing In A Time Of Crisis" in The Issue is Power: Essays on Women, Jews, Violence and Resistance (1992)

- Rita Giacoman is the first hardcore Palestinian feminist we meet. She cites Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own, speaks of the deep need to degender education for the young. She's in contact with Israeli feminists, and she comments-quite Woolflike-"Feminists-both Israeli and Palestinian-interpret movement not in nationalist terms, but in terms of cooperation."

- Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz "I've been to Israel and Palestine" in The Issue is Power: Essays on Women, Jews, Violence and Resistance (1992)

- Reading Virginia Woolf's Orlando was an event... it's all right to make your man turn into a woman, it's all right to have a century of time flow by here and a moment of time flow by there. She showed me various freedoms I could take in writing.

- 1986 interview in Conversations with Maxine Hong Kingston (1998)

- When I read Virginia Woolf's Orlando or William Carlos Williams's In the American Grain, I can feel like I'm dying, or I'm stuck, both in life and in work. I read those books, and then I start flowing again. I'm happy that I can do that for other people.

- 1989 interview in Conversations with Maxine Hong Kingston (1998)

- There's a life force that's in Orlando. There's a light shining from that book. When I feel discouraged, I can pick it up and read a paragraph and feel up again. Woolf covers four hundred years of history, and one person lives for four hundred years. And I thought, "Yeah, I can treat time like that." The way Virginia Woolf uses time makes sense to me. And frees me, too. If I want a character to live to a hundred and twenty so that he can live many connecting experiences, so that he can go from one part of history to another, then I just go ahead and do it. We don't know exactly how old my grandmother is, my mother and my father are, because they have all these fake papers and stories, and so I just went ahead and gave them long lives and didn't worry about their ages. Orlando gave me permission to make them as old as they needed to be.

- 1996 interview in Conversations with Maxine Hong Kingston (1998)

- ("you wouldn't agree with Virginia Woolf that there is such a thing as a woman's prose style?") I don't know. I am not going to disagree with Virginia Woolf about anything. I see her style, which is wonderful. Now there's the kind of complexity that I envy with my whole heart, that kind of weaving. But is there anybody besides Virginia Woolf who can do that particular sort of thing? You see, that way of thinking slides so easily into a sort of sexism that it worries me a little bit.

- 1982 interview in Conversations with Ursula Le Guin (2008)

- ("Has feminism affected your self-concept?") Yes, it's given me more confidence to be a woman. It has helped women be women and not just reflections of men, particularly, as Virginia Woolf said, "magnifying reflections" of men.

- 1988 interview in Conversations with Ursula Le Guin (2008)

- The incredible upsurge of woman writers and poets in the 1980s is a sign that women are finding their voices. They're beginning to talk about their experiences without using a male vocabulary or meeting male expectations. It's sticky, because the language is so male-centered that it excludes much of the feminine experience. Sex, for instance, is always described from a male point of view, as penetration, insemination, and so on. A lot of women still deny that their experience is different than a man's. They do this because it's scary to realize you don't have the words to describe your own experience. The few words we do have we get from our mothers and the women who taught us when we were young. Virginia Woolf says, "We think back through our mothers."

- 1994 interview in Conversations with Ursula Le Guin (2008)

- if your storyteller's Virginia Woolf, you've hit a pretty high-level society.

- 1994 interview in Conversations with Ursula Le Guin (2008)

- as feminist theory began to finally get into my head, and as I began to read what the feminists told me to read, which was my female ancestors in writing-I had always read George Eliot, Willa Cather, and so on, certain writers, and of course Virginia Woolf. I had read Virginia Woolf for years, but as I began to understand what she was trying to say, I was reeducated, it really was true. And I think, I'm so grateful to Woolf and all the rest of them because I think I would not have been able to go on writing, that this pretending to be a man all the time, it was beginning not to work. I'm not a man, but I didn't know what was wrong. I didn't know what this sort of discomfort and feeling of frustration was, and I had to learn how to write as a woman, and there's no doubt about that, and I had to fight a lot of my own training and prejudices.

- 2002 interview in Conversations with Ursula Le Guin (2008)

- I think Virginia Woolf is probably the person whose technical daring and her skill at doing that kind of thing and moving from one head to another head, from one point of view to another, in the years and in the ways, is the most admirable. Nobody has written anything like that that I know. I was fascinated by what she did. She was doing something new in story telling, something new in the novel, by that moving point of view. The nineteenth-century novel does it too, of course, in a very different way.

- 2002 interview in Conversations with Ursula Le Guin (2008)

- Virginia Woolf... it's taken us fifty or sixty years to figure out what she was doing in her novels. We are just beginning to get some good Virginia Woolf criticism, because she was way ahead of her time. Everyone said James Joyce is it. OK, he was it for then, but to me Virginia Woolf is still it, while Joyce is an interesting phenomenon historically. Woolf is still a writer who took risks that we don't even know how to explain. It's a matter of rereading, learning to read, and seeing what is there, instead of what "ought to be there."

- 1994 interview in Conversations with Ursula Le Guin (2008)

- It is also possible to use fictitious characters to highlight an absence, as Virginia Woolf does in A Room of One's Own when she speaks of Shakespeare's talented and fictitious sister, for whom no opportunities were open. I wrote a similar piece about the invented sister of a Spanish chronicler who visited Puerto Rico in the 18th century to make visible the absence of women chroniclers.

- Aurora Levins Morales, ‘’Medicine Stories’’ (1998)

- There's been some change, as is evident by the number of women writers who are read. And education itself has somewhat changed. There's a lot more encouragement, a lot more writing classes. It was the women's movement that gave women in academe a certain strength. If you'd look at the old reading lists, maybe George Eliot, the Bront‘s, Virginia Woolf might be taught. At Stanford, I think it was 1971, they needed somebody [to teach their first-ever course on women's literature], and my name was suggested. Well, I had no credentials. I had never gone to college. And there was quite a to-do about whether or not I had the qualifications. It was supposed to be a small class. I went into this auditorium. It was jammed. There were, I think, four guys, one of whom went out and then came back again and then went out and then came back again. There were over 100 women there, including faculty wives. By and large, none of this had ever been taught at Stanford before.

- Tillie Olsen answering "How has the situation of women writers changed?" in interview with The Progressive Magazine (1999)

- (What women writers, contemporary or historical, well-known or obscure, do you count among your most important literary influences? And is anxiety of influence a notion that applies equally to women writers?) AO: I could name dozens, but here are a few:...Among prose writers, Virginia Woolf above all.

- Our thinking does tend to be dominated—colonized, you might say—by the history of patriarchal thought and language, but it is still possible to think independently if you make up your mind to do it and be vigilant. Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own promises that “if we have the habit of freedom and the courage to write exactly what we think,” we might change the world.

- In A Room of One's Own, Virginia Woolf satirically describes her perplexity at the bulging card catalog of the British Museum: why, she asks, are there so many books written by men about women but none by women about men? The answer to her question is that from the beginning of time men have been struggling with the threat of woman's dominance.

- Camille Paglia, Sexual Personnae (1990), p. 295

- Woolf meant something to me. Mrs. Dalloway, I remember, was the first thing I read. I loved the style; I was very interested in the style

- 1981 interview in Conversations with Grace Paley (1997)

- In rereading Virginia Woolf's "A Room of One's Own" (1929) for the first time in some years, I was astonished at the sense of effort, of pains taken, of dogged tentativeness, in the tone of that essay. And I recognized that tone. I had heard it often enough, in myself and in other women. It is the tone of a woman almost in touch with her anger, who is determined not to appear angry, who is willing herself to be calm, detached, and even charming in a roomful of men where things have been said which are attacks on her very integrity. Virginia Woolf is addressing an audience of women, but she is acutely conscious-as she always was-of being overheard by men: by Morgan and Lytton and Maynard Keynes and for that matter by her father, Leslie Stephen. She drew the language out into an exacerbated thread in her determination to have her own sensibility yet protect it from those masculine presences. Only at rare moments in that essay do you hear the passion in her voice; she was trying to sound as cool as Jane Austen, as Olympian as Shakespeare, because that is the way the men of the culture thought a writer should sound.

- Adrienne Rich On Lies, Secrets and Silence (1979)

- Comparing Jane Eyre to Wuthering Heights, as people tend to do, Virginia Woolf had this to say: "The drawbacks of being Jane Eyre are not far to seek. Always to be a governess and always to be in love is a serious limitation in a world which is full, after all, of people who are neither one nor the other.... [Charlotte Brontë] does not attempt to solve the problems of human life; she is even unaware that such problems exist; all her force, which is the more tremendous for being constricted, goes into the assertion, "I love," "I hate," "I suffer"...She goes on to state that Emily Brontë is a greater poet than Charlotte because "there is no 'I' in Wuthering Heights. There are no governesses. There are no employers. There is love, but not the love of men and women." In short, and here I would agree with her, Wuthering Heights is mythic.

- Adrienne Rich On Lies, Secrets and Silence (1979)

- Virginia Woolf is referenced in this book again and again, both for her work and for her tragic life, which, I suppose, are one and the same...None of my books could have been written without these extraordinary authors.

- Erika Sánchez Introduction in Crying in the Bathroom: A Memoir (2022)

- I enjoyed talking to her, but thought nothing of her writing. I considered her 'a beautiful little knitter'.

- Edith Sitwell, in a letter to Geoffrey Singleton (11 July 1955)

- What is extraordinary is that the hostility the [Bloomsbury] group originally provoked is still with us and is often expressed with the violence of first discovery. In a recent New Statesman review, for example, the English critic John Carey quotes one of Virginia Woolf's snobbish remarks about the lower classes and concludes: "Maybe she was right to make away with herself and leave the landscape clean."

- Alex Zwerdling, 'Bloomsbury Variorum', The Sewanee Review, Vol. 84, No. 3 (Summer, 1976), p. lxxxiv

External links

[edit]Categories:

- Feminists from England

- Atheists from England

- Novelists from England

- Essayists from England

- Short story writers from England

- Playwrights from England

- Autobiographers from the United Kingdom

- Memoirists from England

- Diarists

- Cultural critics

- Social critics

- Critics of religion

- Humanists

- Anti-fascists

- Pacifists

- Socialists from England

- Women from England

- Women authors

- Suicides

- 1882 births

- 1941 deaths

- LGBT people

- People from London

- Women born in the 19th century

- Mental health activists

- Activists from England

- Women activists

- King's College London alumni